Note: Well, this is it folks. The last of the Laird Barron read-alongs. I hope you've enjoyed reading this recent series as much as I have writing them. Once again, I'd like to thank the other contributors, and give a special thanks to u/igreggreene and u/Rustin_Swole, without whom this project wouldn't exist. But as one chapter closes, another begins. While the Laird Barron Read-along is over, I will be working on the Friends of the Barron Read-along starting with John Langan's The Fisherman. This read-along won't be covering everything Laird's friends and inspirations have written, but it will be a look at the works I think are most emblematic of whatever author is being covered.

This read-along also won't be releasing weekly, but instead monthly. As much as I like writing these kinds of essays, it is exhausting, and I do want to write other stuff too. If you'd like to follow some of that other writing, you can join me on www.eldritchexarchpress.substack.com where I post weekly about books, TTRPGs, and horror. Occasionally, I even drop a little original fiction.

One last thing, tomorrow my usual Praetermancy post will drop. I wanted to get this series done this month though so you get two posts this weekened. Anyways, enough stalling. On with the essay!

In the process of writing this essay, I read and listened to The Wind Began to Howl five times, with four of those readings occurring almost back to back. There were two reasons for this:

It's just that good.

It's just that dense.

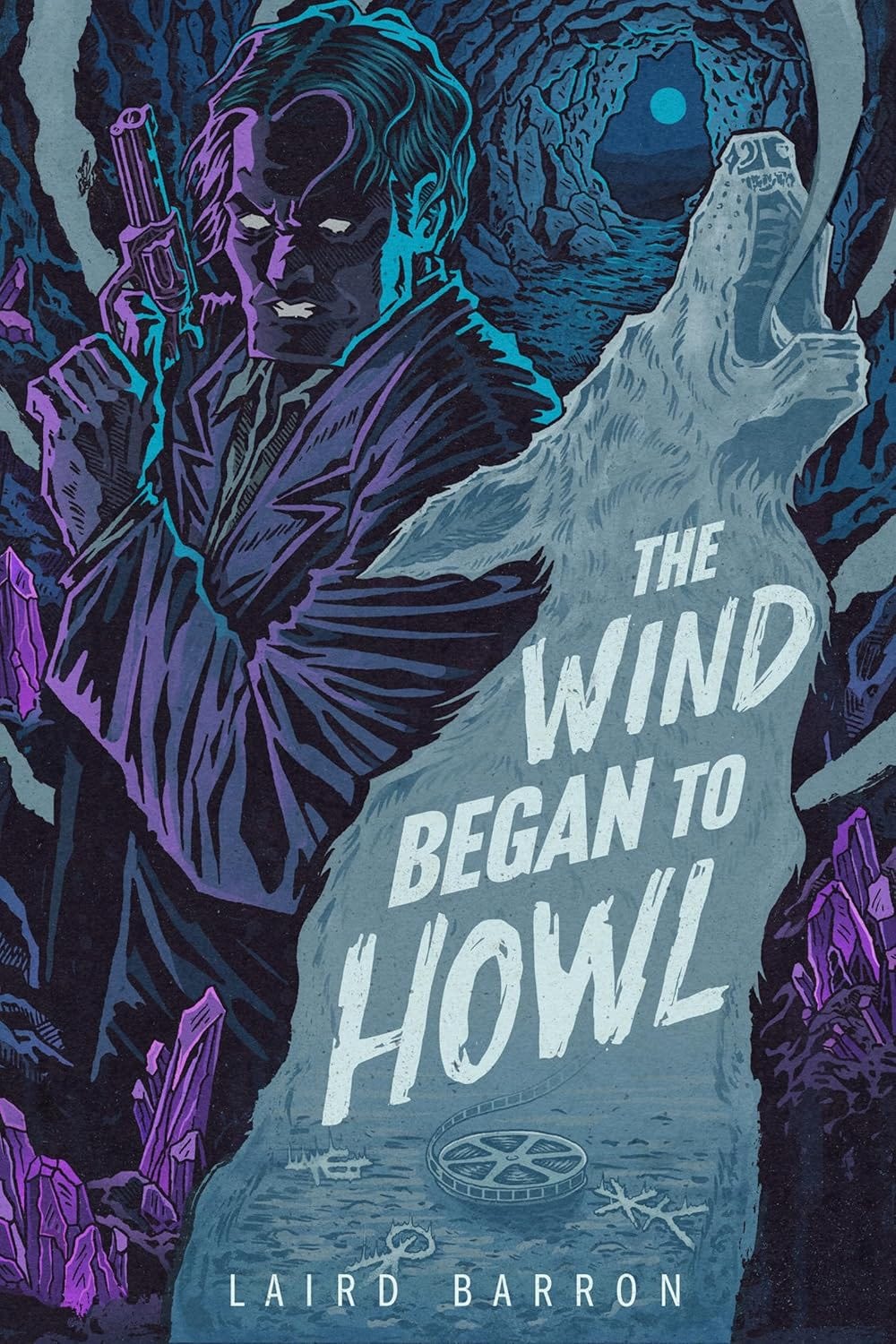

The Wind Began to Howl is packed with references. Some of these are to Laird's own work, some are to the movies and music he clearly loves, and some of these are to ideas and concepts with roots in religion, philosophy, and the occult. All of this is crammed into a little over 40,000 words, or 4 hours if you are listening to the audiobook.

But The Wind Began to Howl is more than just references. If it were just references, it would not be one of my favorite pieces of Laird Barron's fiction. Instead, it takes these references, and uses them to build a point of view that, while nostalgic, is immensely relatable and deeply thematic. It takes a Coleridge story and removes all the fluff, all the extraneous bits that aren't needed, and leaves story gold.

If I have a complaint with Laird's work as a whole, it is that Laird's characters rarely tug at my heartstrings. There are a few, but his style leans towards disgust. Towards contempt. Towards violence. Laird's best stories tend to have poet-barbarians as main characters. Conan types, men and women of action and adventure who encounter the strange and sorcerous and either barely escape with their lives, or don't escape at all. These are not, by and large, relatable people. They don't worry about picking up the groceries, or being a good spouse. In fact, in quite a few circumstances, they are assholes who would be the villains, if they weren't in a cosmic horror story.

The Coleridge series as a whole offers Laird's best character work to date, because it utilizes his strengths while also shoring up his weaknesses. Coleridge is all those things that Laird typically writes well, but he is also more. His struggles against forces beyond understanding are paired with very mundane challenges about how to be a good significant other, a good father, and a good friend. This more effectively drives home the emotional component, and better shows Laird’s full range.

Summary

Part The First

The Wind Began to Howl opens up with one of the greatest opening lines in fiction: "As autumn slouched closer, my tarot card spread had turned up fools, hanged men, and devils." Oh, Coleridge, you have no idea. Marion Curtis wants a word. The aging crime boss is slowly going straight, much to his chagrin. The days of the outfit going around, busting kneecaps and silencing witnesses are dying, and he's had to change with the times. His movie company is clean, and he needs a favor. Sorry, did he say ‘a favor?’ He has a request. Coleridge doesn't do favors, but a request? That he can do.

Gil Findley is a director in need of a PI. His film, The Wind Began to Howl is reliant on a certain music track made by the Barnhouse brothers, a pair of musicians known for their musical experiments. They promised Gil that he could use the track, but his studio won't let him finish the project without a contract saying as much. It shouldn't be a hard job. The brothers are weird, not violent. The fly in the ointment? They're missing. That's why Gil needs Coleridge. Isaiah agrees to help track down the brothers, as well as show up to a party Gil is hosting in a week with Meg and Lionel in tow.

On the domestic front, things are going well in Coleridge's sphere. He, Meg, and Devlin go to a cat party a couple of days later, where they meet several cats, one of whom is named Harley (which I bring up because it will be relevant later). Things go well, but it’s obvious that Coleridge and Meg are being stretched a little thin between their busy jobs and other life events.

A couple of days later, Coleridge begins digging into the Barnhouse brothers more thoroughly. The brothers lived in the Washington state area before joining the military during Vietnam. Upon their return, they moved to New York, publishing three literary thriller novels, and several albums of reasonable popularity. In their downtime, they went spelunking, and intriguingly, helped some archaeologists in Mexico with harmonics tests.

Recon done, Isaiah decides that it is time to bring in Lionel. Lionel, of course, is engaged in his favorite non-alcoholic vice: fighting. He's picked a fight with contractors from a nearby farm. His victory is Pyrrhic, but as he observes, ‘victory is victory’. The two men pay a visit to one Judd Acker, radio program director who has worked with the Barnhouse brothers in the past. He owes Coleridge a marker, but Lionel is there to make sure there's no funny business. Acker reveals the brothers are on the rocks with their old label. It's dead and gone now, but the owner Cordel Harms is a nasty piece of work, known to apply pressure now and again. Krystal Nivens knows more, she was the boy’s girlfriend. Yeah, apparently they shared. Gross. Lastly, he lists Todd Lyra, the Barnhouse's drug connection. That's it. That's all she wrote. Or all Acker knows at least.

Coleridge decides to visit Lyra first. He doesn't make a good first impression, and Coleridge ensures the man knows he "poked the wrong bear." After that, Lyra spills beans. He doesn't know where the boys are. Krystal Nivens wasn’t just their girlfriend. She picked up the drugs. He also expands on the Barnhouses. On top of caving and music, Roger was trained in astronomy while Kenneth studied folklore. Both are occultists and amateur magicians. Creepy motherfuckers too, as Lyra tells it. The type to join a cult, or more likely, found one. Leads drying up, Coleridge places his most reliable low lives on the task of watching Nivens.

While said lowlifes do their thing, Coleridge attends a party/private viewing that Gil Findley has organized. He introduces Coleridge to his lawyer, a man named Cluppitch. If he sounds a bit like a fish, don’t worry, Coleridge smells something too. Perhaps it’s because Cluppitch assures Coleridge that everything is above board. Very boilerplate. Also, don't open the contract until it’s ready to hand over. Please and thank you.

The conversation done, Gil introduces Coleridge and Lionel to Stanley Fischer and his girlfriend Sandel Urban. Fischer knows the Barnhouses’ but he was also a movie director once upon a time. Only other thing you need to know about Fischer? He doesn't like dogs.

Gil decides to show a rough cut screening of The Wind Began to Howl. We don't see much of the movie, Urban vomits before it goes very far, but based off of Gil's plot sounds like a bunch of Laird's previous work blended together. Scatological, gory, and behind it all a music track composed of mostly infrasound. This naturally leads to a discussion of conspiracies and the CIA. Urban admits to having been an asset once upon a time. She tells a story about being stopped by a Middle Eastern warlord while their stuff was ransacked. The warlord let them go after finding a copy of "The Barnhouse Effect" inside their luggage, but only after he spent an hour going over western music theory. Urban declares the brothers are cursed. The others disagree, saying that they are merely unfortunate. Fischer thinks that the brothers are off trying to reverse their misfortune by creating a new album at their hidden studio "Wails and Moans." He doesn't know where it is, but he knows what it's close to. A 'camping' trip is arranged.

Coleridge promised not to open up the contract until the Barnhouses agreed to sign it. But you know, big guy like him: fingers slip, envelopes rip. Oops. Of course, he was going to read it and have his lawyer, Red Mclaren, give it the once over. As Meg points out, he's a "lug" not an idiot. There's nothing there though, but Cluppitch is mobbed up, so Red isn't going to do any more digging for Coleridge. Sorry. No problem. About the time the meeting ends, Coleridge's flunky texts him letting him know that someone is breaking into Krystal Niven's apartment. Coleridge to the rescue. It doesn't exactly go well for him. Coleridge is big, mean, and experienced but the two intruders he runs into are not slouches, and age is catching up with him. Krystal pokes her head out once the intruders have fled. Her words of greeting? "Those guys were really kicking your ass."

As always, the cops arrive a few minutes too late and the intruders are in the wind. Coleridge explains his presence away, and Nivens backs him up, rounding on him once the cops leave. She knows who the intruders were. Cher and Pulanski, as Coleridge has nicknamed them, work for Cordel Harms. All three were part of the Alphabet Soup at one point or another. The Barnhouse's former producer isn't happy they abandoned him. The boys disappeared in part to get away from him, but Harms is all too happy to harass Krystal into finding out where the boys are. A knight in shining armor, Coleridge is not, but he puts Nivens up in a hotel room until things get sorted before returning home. Apparently Meg has a thing for bruises.

Part The Second

The expedition begins well enough. Coleridge's bruises trouble him, Lionel and Krystal loudly shout over the music, and poor Gil has to settle for being in the back seat stuck with the two of them. Minerva has the time of her life in the front seat though. Lionel once again proves his dubious taste in women by hitting it off with Krystal Niven. The cabin is a favorite of the Barnhouse brothers, and they've rented it before alongside Fischer and Urban. The conversation that evening turns towards Coleridge's running with Polanski and Cher. Urban recognizes them as former intelligence agents known to do freelance work for Harms on occasion. Harms in turn has freelanced for a laundry list of big names. Zircon, Black Dog, Sword Enterprises to name a few. Last time Fischer and Urban were at the cabin, Fischer found where the Barnhouse's kept their journals. He pulls one out to show Coleridge.

The book is part journal, part grimoire. It reveals the brothers have ties to, among other things, the Jeffers Project and Campbell and Ryoko, and the Book of the Void, as it is labeled, also has mentions of Anvil Mountain and Harpy Peak. Near the end, it also contains a "techno-ouroboros, almost, but not quite biting it's tail." along with another reference to the events of Worse Angels. Coleridge retreats outside and muses "What if Harm's isn't looking for the brothers? What if he already has them?"

The next morning the search for the brothers truly begins. Initial results are decidedly negative, though Coleridge does meet a young hotel manager who promises to look into things for him after some decent pay. Soon after, Coleridge strikes gold. Or maybe gold strikes him. Rodger Barnhouse is eager to visit the nearest tavern. The conversation does not go the way Coleridge expected. Rodger speaks in riddles, implying much and saying little. What he does say is frightening enough. Krystal has split loyalties for starters. Then he jumps directly into listing the stats off the back of Coleridge's baseball card. Not the stats on his website, but the real stats. The headbutting with Zircon and the Redlick group, the hatchet man act, etc. Things Barnhouse shouldn't know. Roger refers to himself as "genius loci" when the time comes to explain himself. "Tom Bombadil... was the elite. I'm almost elite. You might get there." This he says before launching into his life story. It boils down to this: Coleridge has once again stepped right into the worst kind of shit. Harms has had his eye on the Barnhouse's for decades. Since they were kids. He isn't letting go of them easily. He still has Ken, but Rodger got away. Rodger won't sign, but he doesn't say Ken won't. No way to find out unless Coleridge can rescue the other Barnhouse. 'Come ready for bear. You've almost found Shangri La, Coleridge.' Barnhouse steps out. Coleridge couldn't stop him if he tried.

The next day, the group continues the search for Wails and Moans. Rodger is in the wind, or given his... abilities, he might be the wind itself. Rodger didn't reveal the location, but he left hints. Coleridge pieces it together. Harley. The name of the cat from the party he attended with Devlin and Meg. James, the helpful clerk from earlier, helps put the last pieces in place. There's a place in the woods called "Harley House." There's also something of a theme park nearby. Coleridge sends, Gil, Fischer, and Urban home while he, Lionel, and Niven go to look at Harley House. Harms ambushes them, revealing that Krystal used to work for him. Now she just works for herself. Fortunately, Niven called Urban back, and Urban brought Fischer and Gil with her. A counter ambush. A gunfight ensues, and Coleridge and Lionel emerge victorious. Cher, Polanski, and Harms don't emerge at all.

It's time to call the police, but Coleridge won't leave without finding Ken. He and Lionel head toward the theme park and find a bunker hidden in the mountain side. Coleridge descends. He finds Ken, barely alive, barely sane. Tortured for reasons beyond Coleridge's understanding. Nobody is signing nothing. Fast forward a couple of weeks. Ken has been remanded into the custody of the federal government. Gil's project is in development hell. Urban and Fischer are globetrotting. Score half a point for the good guys. Thing is, there's something about that contract. Rodger and Ken wouldn't sign it for a reason. Coleridge takes another look. This time with firelight. It's not the kind of contract that's legally enforceable. But there are other laws... Older, darker laws. Ken and Roger dodged a bullet. Coleridge once again, has stepped in shit. "Abracadabra."

Analysis

The Wind Began to Howl is some of Laird's densest writing to date. There are so many references, so much thematic imagery that this book should be a mess to read. Instead, it's remarkably cohesive. Remarkably creepy. Remarkable in general, if we are being honest.

The most straightforward references are to movies and music from an era well before I was born. I won't linger on them for very long, other than to say that it's clear to me that The Wind Began to Howl is something of a love letter to those artists, directors, movies, and albums. Every chapter has at least one reference that I could spot, and most have 2-3. It should feel cheap. Instead it feels thematic. Intentional. The references are nostalgic, but this nostalgia isn't just skin deep. It serves a purpose, and that purpose is to let Coleridge feel his age. Reading this book, I was reminded a lot of how my dad, as he approaches retirement and with more free time than he’s had in at least 30 years, has returned to listening to the albums and watching the movies of his youth. Coleridge (and I suspect to a certain extent, Laird) are doing the same thing. Harkening back to the days of yore is a time honored tradition among the middle aged.

In the hands of another author, this might be a shibboleth, a kind of password meant to keep out "the youngsters." But in Laird's hands it's an invitation. Coleridge's struggles are ones that are probably familiar to most people from their mid-twenties on. I will turn 29 the day after this write-up is posted. But despite the difference in our ages, I have plenty in common with Coleridge. The references are different, but the context is the same. My nieces and nephews are already growing up in a world wildly different from the one I grew up in. My generation is already dealing with the same kind of nostalgia that Coleridge is. His descent into occult realms mirrors my own experience with growing up, and losing innocence. Aging has always been a theme of the Coleridge books, but I don't think any do it quite as well as The Wind Began to Howl. The series is a meditation on the process, but this book specifically engages with that meditation in a way that is both effective and inviting.

If that were all The Wind Began to Howl was about, it would be a really good book. Instead, it's an excellent book. But to explain why I need to change perspective. Instead of looking at events through Coleridge’s eyes, let's look at them through the Barnhouse’s. From the beginning, all these men want to do is be free. Free from their father. Free from to create and write. Free of Harms. They explore magic, they explore the occult, but unlike most figures in Barron’s bibliography, they aren’t looking for power. Like Coleridge, they are looking for escape.

Their magical expertise binds them. First they run into Harms, then they get involved in the Jeffers project, and the experiments in Mexico. They run into a who's who of Barron's biggest names and faces. Instead of getting out, they get dragged deeper in. Even when imprisoned by Harms, they are hunted by other factions. The federal government seems all too happy to get Ken, and Coleridge serves a faction that even we the readers can’t really identify. They are hunted. When we look at them, who is it that we are supposed to see?

There are two people.Firstly they serve as an obvious mirror for Coleridge. He is also someone running from his past, who seeks freedom. But Coleridge is bound to Marion Curtis. He’s performing the man’s ‘request.’ Like them, Coleridge isn’t proud of the things he’s done. He wants a life with Meg and Devlin. But he is unable to escape his darker nature, and his curiosity leads him to places that are better left unexplored.

The second person I think we are supposed to draw parallels to, is Laird. Now, as a reader it can be dangerous to draw conclusions about an author’s life by reading their fiction. Don’t read too much into this idea. Don’t overthink this. I don’t think this is a message Laird is trying to send, but a theme to be explored. That theme is “Creative Freedom.”

Here’s my argument: Laird shares a lot in common with the Barnhouse brothers. This is nothing new to his writing. Indeed, Laird shares a lot in common with many of his protagonists. But the specifics here are interesting, and I think Laird shares more in common with the Barnhouses than he does any of his other characters, bar Coleridge.

Like the Barnhouses, Laird moved from Washington State to New York. Like them he wrote three thriller novels and then got dropped by his publisher. To me, I cannot help but see this as semi-autobiographical. To be clear, I don’t know how many copies Coleridge sold, but I doubt it's on the best-seller lists, otherwise, I think Putnam would have published The Wind Began to Howl, instead of Bad Hand. From the beginning, Laird has been trying to push boundaries with his writing and create more ‘weird stuff.’ Coleridge echoes this. When the series began it was fairly straightforward Noir. Now, in this entry, we are firmly entrenched in horror and bordering on adult urban fantasy. When asked what was keeping him from writing the ‘weird stuff’, Laird responded that he needed to put food on the table. The market, he thought, just wasn’t there. Recent years, I suspect, have seen maybe not a change in perspective, but an increased willingness to push at the boundaries.

Audience expectation can be a chain. A lot of fans aren’t interested in following an author when they step away from a series or genre. Among us, the hardcore fans of Laird, the Coleridge series is among his best. But to more casual readers, it’s not surprising that they might look at Imago Sequence and then Coleridge and go “Eh, I’ll pass. I prefer the Cosmic Horror stuff.” Every attempt at experimentation is a risk for a published author. It takes a lot of effort to loosen the chain of audience expectation, so you can have some breathing room. The Wind Began to Howl is in part an experiment. It’s another way he can push at those chains.

At the end of it all, the only way out for the Barnhouses’ is ascension. This isn’t a new theme of Barron’s, but this time, it feels personal. Coleridge is told, “Genius Loci… Tom Bombadil... was the elite. I'm almost elite. You might get there.” The only way out it seems, is through. Or is it? We see three outcomes. For Rodger, the answer is ascension. Ken fails to ascend, and is taken by the feds to an asylum where he is to be a dancing bear, poked and prodded at by the powers that be. Lastly, there is Coleridge. For him there is no guarantee one way or the other. The question is, can he step off the path entirely? Or is it too late? Has he crossed the Rubicon?

I don’t know. If we know one thing about Laird’s writing, it is that Ascension has its downsides. Perhaps, as Rodger posits, the only way out is through. But the price of failure is high. Is there a third path, yet to be discovered? Maybe. But personally? I think Coleridge is doomed. The only questions remaining are what form will that doom take? And how many loops around the ring of time until he finds it?

Connections

As I said at the start of this, there are a lot of references in this novella, too many for me to keep track of. However, there are a few that are directly relevant to Laird’s body of work:

The tavern named 'The Fisherman' may be a reference to John Langan's novel and the restaurant that features in it.

The Ornithologist is referenced in several places throughout Laird's mythos, but the most notable is in the Coleridge saga.

Gil Finley's home is the same one that features in “Joren Falls,” “American Remake of a Japanese Ghost Story,” and “Not a Speck of Light” among others. His film Torn Between Two Phantom Lovers, is also referenced.

Now, this might be a bit of a leap, but The book of the void has the image of a "Techno-ouroboros." We've seen ouroboros imagery several times throughout the Laird Barron readalong: It shows up on the cover of The Black Guide (Mordedor de Caliginous), on the cover of The Children of Old Leech, and just about every time the children are brought up. Coleridge might not make the connection, but I think we can safely assume a connection of some kind. This might be AU old leech, or it might be the original version, just morphed by the Barnhouse brothers perception.

Esoterica

There's a lot of foreshadowing in this one: little references to signing the devil's contract even before Coleridge has a contract for the brothers to sign, and well before the revelation that it is actually a fiendish contract. Krystal Niven is the perfect name for someone attached to two people who study harmonics in rocks and caverns. Lionel and Coleridge both suffer from visions and nightmares throughout the story. It's almost too much. Almost. Instead all this leaves a kind of unsettling atmosphere.

It’s also an interesting thing to look at Coleridge as a villain in this book. The Barnhouse Brothers are explicitly Coleridge’s targets. He is told they must sign by any means necessary, and he is willing to do that. It’s only once things start going off the rails that he gets the chance to be a black hat hero again. This return to heroism is only because Rodger Barnhouse sees something in Coleridge and diverts his path. There is a universe where Coleridge is the one torturing Ken to sign. The line between hero and villain is occasionally more tenuous than we would like to believe.

Links

If you would like you can buy The Wind Began to Howl on Amazon using my affiliate link.

Similarly, if you’d like to support Laird directly you can do so at his Patreon

Also, I must once again shout out u/igreggreen and the team over at the Laird Barron subreddit, where you can read more of these essays on every one of Laird’s collected stories.